Replica Eames Dining Chair

Replica Eames Dining Chair

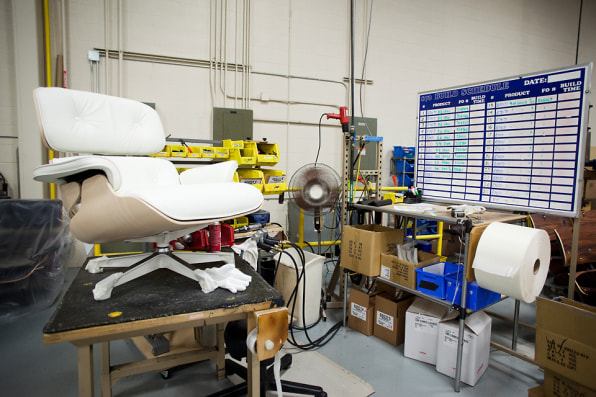

Last year, I visited the Herman Miller factories and manufacturing partners in and around Zeeland, Michigan, and my first stop was at the astonishingly efficient factory that turns out the famed Aeron chair. Using a continual improvement management process learned directly from Toyota manufacturing gurus, Aeron production efficiency has improved by 500% since it was first introduced. All of which is a marked contrast to the Eames classics that made Herman Miller famous. As much as technology has advanced, and as much as the status of the American worker has morphed, the process of making an Eames lounge or a LCW chair remains painstaking and thoroughly human.

For the most part, these processes are virtually identical to those developed by Charles and Ray Eames over 65 years ago. But in very quiet but telling ways, they're also better: The curing for binding the plywood has changed; the niggles of creating a "shock mount" that joins a metal leg to the body of a curved piece of wood has been perfected. (If you've ever seen an old Eames lounge chair, that shock mount is the culprit for the arms usually falling off after 20 years.) And the cow hides used in the chairs are cut by an enormous computer-guided machine, which scans the leather and figures out exactly how many upholstery pieces can be wrung out of it, and cuts the pattern accordingly. It looks like an oversized air hockey table. (You can see that process at 0:33 in the video above.)

But all of the efficiency is still guided by humans simply because the materials are natural and don't lend themselves to automation. Any given cowhide might stretch twice as much as the next one, simply due to natural variations. A seamstress has to adjust accordingly. The wood grains for an Eames lounge don't automatically match up–a human has to be there to eye the various pieces and make sure they make sense when paired together.

That sense of ownership and the conferred glow from manufacturing true classics, according to Mike Kuperus, the plant manager at the factory, results in virtually no turnover among the employees. "People who have been here for 10 years will still come to me and say, 'Look at this before I box it up,'" he says. "They appreciate the pieces as much or even more than the end consumer." With that in mind, seeing the pieces still rolling off the lines is a little amazing: Consider not just how many rear ends have sat in the Eames designs but how many generations of workers have made a livelihood out of bringing them to life. That's as great an example as any of the good that good design can leave in its wake.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/1669956/watch-the-handmade-process-behind-your-eames-chair

Tidak ada komentar:

Tulis komentar